We don’t take the expression, “It takes a village” as serious as we ought to. Maybe you do and I’m whining about how we should take it more seriously to the choir. Well, if that’s the case, now you know I’m fully on your side. But, if you’re not, of if you haven’t really thought much about the expression, think about it with me for a minute. Far too often when somebody is saying, “it takes a village,” they seem to be commenting on an individual kid or an individual circumstance, as an outcome, when it’d be better to talk about the village as a whole.

Not because every citizen is going to be a perfect model citizen. If anything, you don’t want that to be the case. Because diversity’s a perk. A village has to be a little messy in how things play out, because life is a little messy like that. But, the village also has to look out for one another, largely by keeping the worst of the worst out, and—by letting communal curiosity invite the most interesting opportunities in.

Jon Solomon is a reasonably well known indie-music personality. He’s got a famous 25-hour Christmas show. He’s also got a 3-hour weekly program that, it’s iconic. You should check it all out.

But more than anything, Jon Solomon has some beautiful Steve Albini stories. I’m transcribing a snippet of one here for you (and for me, because I want to be able to find this again in the future):

Steve Albini’s band, Shellac, agreed to play in my parents living room in 1993 because I sent them a fax. I still have the fax. My mom worked the door. $5 cover. Gave all of the money to the band, only after arguing with Steve when he tried to give us back $100 bucks for the use of our home. I still meet people to this day, who I personally don’t know, who were in my parent’s living room that evening.

There is something to be said for walking into your parents kitchen and finding Steve Albini drinking a cup of coffee, explaining something about Chicago neighborhoods and architecture to your mom.

A few months later, I would ask Steve if I could intern for him at his home on Francisco Street in Chicago. He said yes. The whole neighborhood smelt like strawberries some mornings, chocolate or butterscotch others, and thus, 1/48th of my college degree was earned curling audio cables, alphabetizing records (ex. First World War II, Second World War II…), and sitting quietly in the living room, rubbing root beer extract on and assembling Shellac singles, while the likes of, I don’t know, Guided by Voices and Spitboy watched TV.

He lent me a book about audio waves. I understood none of it. I believe I was the studio’s first intern, but maybe, it was this guy Fred…

The stories continue. It’s a music education. It’s a community education. It’s communally experienced. It took a village.

Solomon was there for the famous prank, where after Jerry Garcia died, somebody published a phone number on a flyer for grieving hippies to call, that promised to take the messages and pass them on to the Garcia family. Albini famously hated hippies. Not in an especially mean way, just in a loathed sub-culture way. If you didn’t already figure it out, the creator of the fliers used Albini’s home phone number for the grievance line. The calls came in at all hours of the day for weeks, and weeks, and weeks. Hysterical.

Solomon talks about the “friends and family only” release Shellac once put out. You couldn’t buy one, they were just special for people they wanted to making something special for. He tells about how excited he was that he got a copy, and maybe more so, how excited he was that they gave his mom one too. Hold that in your head and your heart for just a second.

His time around Albini gave him the “Keep your head down and do the work” ethos he carries with him this day. And he talks about the disagreements too. Regular arguments and stubborn stances, like claiming not to like any hip hop. But again, “it takes a village” is as much about what gets let in versus what gets kept out. Different people controlling different gates can be massively outcome shaping. The work ethos and the deliberate ethic of personal standards form systems. They can be progressive and conservative all at once, without breaking down.

A few more quotes from the piece,

He [Albini] did a lot of things for the sake of doing them if they seemed interesting.

Sometimes we say things that aren’t true because they’re funny. We call this: comedy.

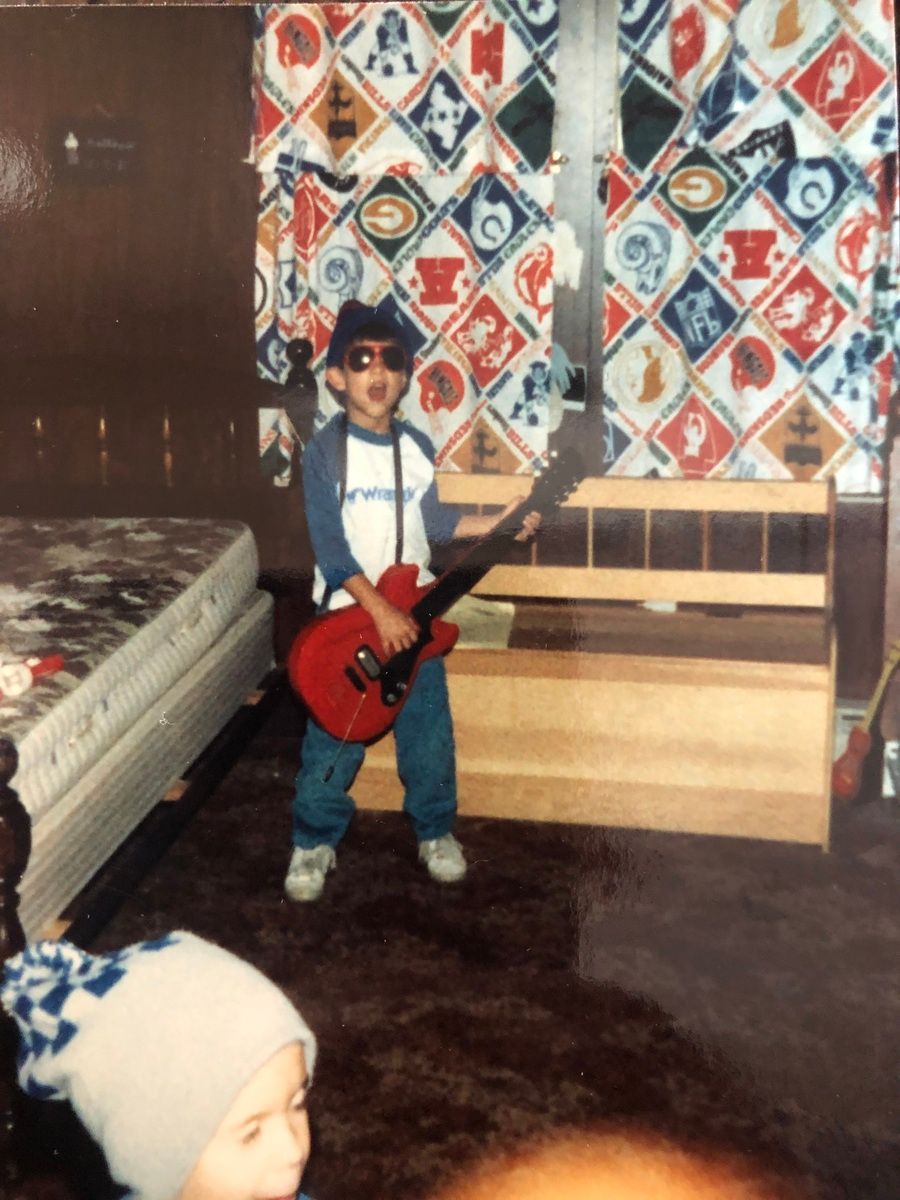

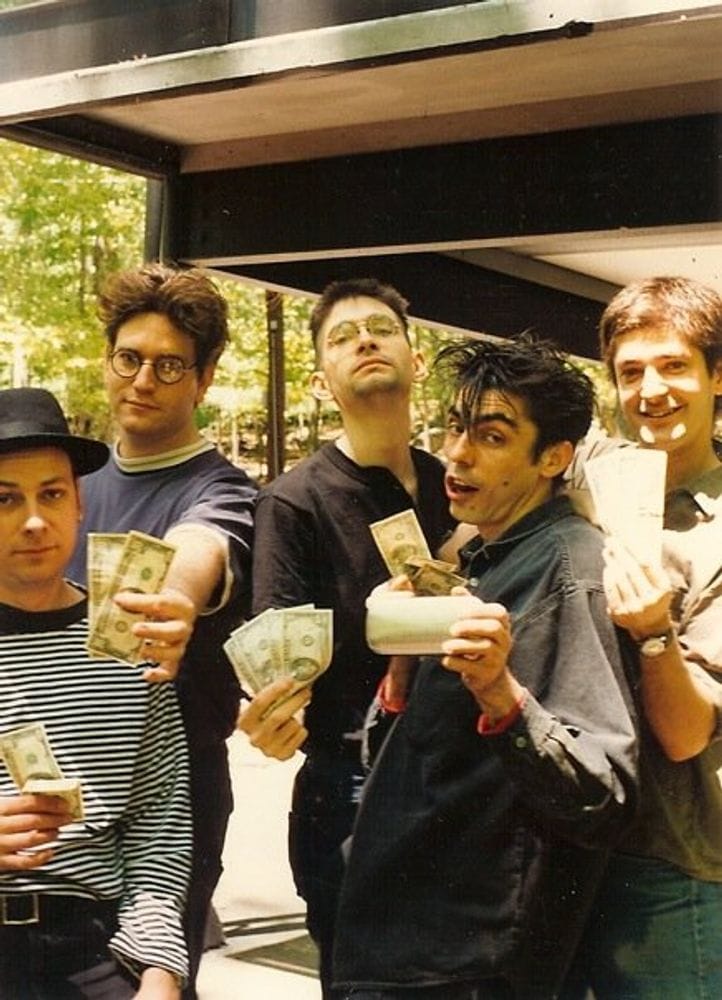

Jon Solomon lost a friend, colleague, and mentor when Steve Albini passed. His tribute moved me. This picture, from Solomon’s driveway says it all. Who wants to live in a village that can’t find something interesting to do, that can’t say things that aren’t true, that can’t have a laugh?

credit: Jon Solomon, Keeping Score At Home website

You can listen to Jon Solomon tell this story on his radio show via the website:

h/t Conor Platt for sending this one in!