Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s great observation was that people make choices between descriptions of things, not the things themselves.*

Imagine I need to pick a painter for my house. You should know, I am not particularly handy, and wouldn’t exactly know how to independently assess a painter’s work. How should I pick who to hire?

Like most people, I would ask some friends and family who they’ve used and maybe look online. Inevitably a few people would come and give me quotes that I’d then compare. Ultimately, I’d end up asking my gut which person I felt the best about.

Note how objectively lacking my assessment is compared to the subjective decision-maker that is my gut. Still, I’d make my choice.

As Kahneman and Tversky made clear – I have not chosen between painters, I’ve chosen between my own assumptions. I’ve assumed that my “positive gut feeling” is equal to the person “probably being a good painter.”

Now, the REAL question is: does the painter in my scenario know this? Is he/she making sure to capitalize on my gut logic?

Our job, no matter what we are doing (painting houses or performing brain surgeries) requires us to communicate a description of the thing we are trying to do to people who understand less about the thing than we do. It doesn’t matter how small your job is – if you interact with even one other person, your job is to anticipate quirky equivalencies like these.

Put your marketing hat on, let’s explore this a little deeper.

Here’s a funny insight in to the way our brains are hardwired: if we don’t know what something is, we automatically substitute something else for it in our minds. We, as humans, have an innate need for things to make some amount of sense. Because we’re lazy too – we want it fast, and with minimal effort.

Have you ever mistaken a stick for a snake? That’s an example of this evolutionary pattern matching in action, and here’s the thing – it extends into every aspect of our lives.

While we are going to set the basic errors aside,** we are going to focus on the concepts of “framing” and “attribute substitution.”

When we say “framing,” imagine a picture frame around a picture. Understand that the context for presentation matters as well as the content itself.

When we say “attribute substitution,” imagine the description you would give to something you didn’t recognize. You would use those same adjectives to describe something else you did recognize.

Let’s use an example: Imagine you’re an environmental activist. You’ve just been asked, “To please donate to the McBean Foundation, which saves the endangered Star-Bellied Sneetches from extinction.” You have no idea what a Star-Bellied Sneetch is, but let’s focus on what is familiar about this request: donate, foundation, saves, endangered, from extinction. The “ask” has been framed in a recognizable way, and the attributes of a Star-Bellied Sneetch can pretty much be inferred. You simply must help! Never mind that both McBean and the Star-Bellied Sneetches are fictional Dr. Seuss characters, this is framing and attribute substitution in action.

Before we describe something to anyone that may or may not understand the topic in the way we do, we should ask ourselves about how best to frame it and provide attribution so that they can make an informed decision. We must do so with noble intentions, and we must be aware that not everyone has noble intentions in mind when they do the same to us.

Since we make choices between descriptions of things, and not the things themselves, we must be keenly aware of these surrounding clues that our brains will automatically use to make something make sense.

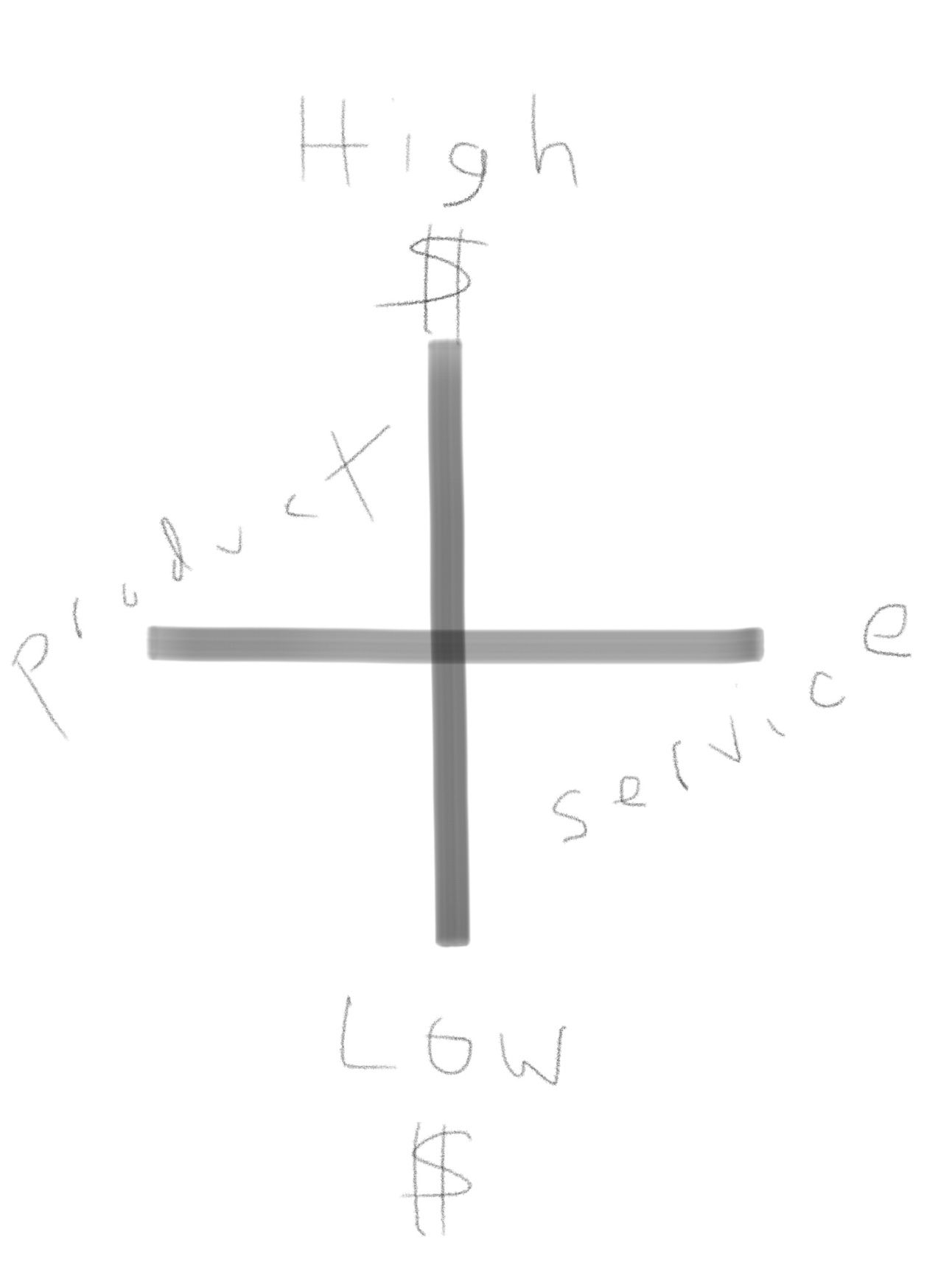

Before we attempt to describe whatever product or service we are offering / being offered, it may be helpful to place it on this graph.

Let explain my poorly drawn graphic: From left to right on the x-axis, we have “products” on one end and “services” on the other. From top to bottom on the y-axis, we peak at “high-priced” and drop to “low-priced.”***

Let’s make an example within the same industry so we can start to think about how things can relatively co-exist, and why thinking this way matters greatly.

In the top left (high-priced product) is a fancy steak dinner. In the bottom left (low-priced product) you have a fast-food hamburger. In the top right (high-priced service) you have the fancy steak dinner serving five-star restaurant. In the bottom right (low-priced service) you have the fast-food drive through window.

We can place anything (really, anything) onto this graph and start to understand how/why people choose it, how it is framed, and what its key attributes are. It should stand out right away that in most cases there is a bridge between the product and service, usually laterally (high-prices good + service, not high-priced goods + low-priced service), although diagonal examples do exist as well.

Take some time to think about this relationship, and ask these questions about either your own job / company or those that you interact with: how do they describe themselves (ex. advertise), how would you describe them (what value do you see/receive?), and (the most important meta question) does their self-description and your independent description lineup – yes/no/why?

How do you solve this fundamental problem: it’s hard to stand out from the group.

People don’t know or understand what we do or why we’re different. Maybe they do after we explain it, but even then – we know they walk away using self-talk to convince themselves why we and/or our products are or are not “worth it.”

When we don’t frame the “why” correctly, they make assumptions. When they don’t understand our assumptions, attribute substitution kicks in – and they start to find their own adjectives.

If we think just in terms of how high / low priced or scarce / abundant our product or service is, we can start by defining it by what it is not.

Jacobi, the famous mathematician (via Charlie Munger, the famous investor), reminds us to “invert, always invert.” He’s onto something.

When you want to sell your steak dinner – try appealing to the negative emotions associated with eating at a fast food restaurant. “Picture the crying kids, the stress, the teenager-prepared garbage food – we are the opposite. A quiet room, lush upholstered seating, we’ll pour your wine, and oh, our tender steaks…”

When you want to sell your drive through hamburger – try appealing to the negative emotions associated with eating at a fancy restaurant. “Picture your kids destroying the table, agitating the so-called sophisticated guests, waiting forever for your food when all you want us just to get the meal and go…”

Fundamental truth: if you can pick the framing and suggest the attributes, you can always stand out from the pack. When in doubt, just invert.

Every successful business tells a story that differentiates themselves from the competition in their customers’ minds.

While differentiation boils down to telling a story, there are 4 key elements that every business story can focus on (via marketing master Seth Godin): Comparison, affiliation, ritual, and fear.

The real pros get multiplier points by being conscientious of how these elements frame and describe the individual attributes of their product and/or service. They also know that explaining what something IS NOT can be as powerful, if not more, than trying to tell someone what something IS. They do this by remembering the difference between high-priced (scarce) items and low-priced (abundant) items.

Let’s break down each of the elements.

Comparison: what should we compare this to or contrast it against? Think in “is / is not” terms.

Affiliation: who does having this product or service put us in rank / on level / in a tribe / in a foxhole with? What about who does it separate us from?

Ritual: how does this experience remind us of other positive experiences?

Fear: what fear does this alleviate?

Now we can make an example of how everything fits together. We’ll consider how a luxury car company would market themselves compared to a used-car dealer. No name brands necessary.

Luxury Car Company:

Comparison (broad attribute list): consider these popular tag lines: power, beauty, and soul; power, driving, and pleasure; the ultimate driving machine. With luxury, high-priced, or scarce items you don’t want to mock non-competitors that aren’t considered in your league (no one likes a bully), but you can knock a known competitor. The goal is to fill the consumer’s mind with adjectives that suggest, “this is the best of the best.”

Affiliation: remind consumers of “who” drives your cars. My favorite examples are how kids / pets / non-drivers are portrayed in these commercials as signals for who is affiliated with this elite group. Do you think Matthew McConaughey and his dogs are going to be ordering sushi from the back of a 2 door family sedan?

Ritual: It’s an unwritten rule – you never show or discuss the daily commute and gridlock traffic, you instead remind them of “driver heaven,” going fast on a winding road through the hills, making killer turns, or… anything that suggests the ritual of driving is related to these peak experiences.

Fear: you do want to be in this club and stand out from everyone else, don’t you? You don’t want to be excluded from driving excellence, do you? You can keep up, can’t you? Scarcity threatens exclusion and missed opportunities.

Cleanse your palate, let’s look at the other side.

Used car dealer:

Comparison: Consider these common tag lines: honest; no hassle; everyone gets approved; no credit? No problem! Used car dealers want you to feel like you can trust them to help you make a big decision that you need to make. The comparison is all about pressure alleviation through a “safe” environment.

Affiliation: everyday people, real people, regular people, people who need some help – NOT those fussy fancy car people, but the sensible car you want and need and can afford. Again, watch for the non-drivers in these ads. These commercials feature kids who need to get to soccer games, messy dogs, etc.

Ritual: the peak experience isn’t the driving of the car, it’s the worry-free sales process. “You’ll get a good deal, we’ll get you approved for a loan, and you won’t end up with a lemon” is the focus. If the ritual is done correctly, people will come back.

Fear: you don’t want to get ripped off do you? Taken advantage of? Swindled? Denied for your bad credit history? Have the car breakdown next week when you need it to last almost forever?

Take a moment and reflect on these scenarios. Do you notice how they are both pretty appealing? Do you notice how they both make compelling cases?

There’s a beauty in communicating an item well. There’s a beauty in understanding something intuitively because we aren’t fishing for our own adjectives. We like when things click. We’re lazy after all.

There are lots of things in our daily lives that we don’t fully understand. We all make choices and decisions based on descriptions of those things. Sometimes they’re our own ideas, but often times they’re ideas that have been influenced by others. If we really want to make the world a better place, then we need to be aware of how these mechanics work.

It’s a big task to stay aware of all these details, but it’s the only way to create “good” products and services, and vet the “bad” ones out of our own lives. It’s a big task, but we have to be up for it.