Art imitates life. To fit 5 decades of life into a piece of art though, especially in barely 2 minutes, deserves some celebrating. I’m not surprised to find it coming from Nas and DJ Premier, but the more I reflect on how it happened, the more I’m loving it.

We’re going to talk specifically about the song, “Madman” off of Light-Years, by Nas and Premier, but I feel like it deserves some extra background, first.

The past few years, we’ve enjoyed something of an epic run of Mass Appeal releases, showcasing mostly good NEW work from legendary/legacy artists. It feels like, it’s the system and pro-artist arrangement the blues artists never had, without turning into what the jazz artists only sort of got, in that none of these Mass Appeal releases have the art-conservatory vibe that almost always turns cool into commercial museum feeling.

How we got here and why this is working as well as it is deserves to be a bigger story. There’s a lot of Gen-X energy in this one, and a notable lack of Boomer BS-ing. In other words, people are making art AND getting paid without any of it feeling like a pure money grab, so - I’m happy.

The Mass Appeal story goes back to the late 90s, when it was a cool AF magazine. Think graffiti, mostly. Very underground, very punk-zine energy meets Complex, mostly because it straddled that line between art and vandalism (I guess that’s the best way to explain it, now?) and it just was super cool to leaf through. Clearly, it was niche popular at best. If one friend had a random copy they got from some unknown record shop, you’d look at it cover to cover six times over and hoped you’d run into a future copy when you were out and about. As a commercial entity, it was just a magazine though. So when the internet showed up, like many magazines, it died off.

Circa 2010, a creative marketing agency/music label guy named Peter Bittenbender got involved in acquiring the name Mass Appeal and relaunching it as a broader media company. He had a reputation, taste (hence wanting the Mass Appeal brand), and a wild set of ambitions. By 2012, one of his prior creative partners, Sacha Jenkins joined him as well. If Bittenbender was the business and structure guy, Jenkins represented a deeper sense of art and storytelling. Jenkins’ work had roots all the way back in literal graffiti zines too (look up Graphic Scenes & X-Plicit Language - deep cuts!).

By 2013, they arranged a co-investment with Nas, bringing the artist/businessman in as co-owner, and in short order turning Mass Appeal into a full on media platform. They could do design. They could release music. They could do events. And they saw what was coming next.

Here’s the Gen-X point. This is where it could have been a cash grab. You have some legacy artist power, you push out a commercial polished product or three, and you do it for you. And they really didn’t do that. Like, almost at all. Instead, and I am crediting Bittenbender and Jenkins extra for this, they leaned into creating work that could help bring attention to and lift entire communities of people who contributed to the culture they were celebrating, but without the levels of success, were quickly being forgotten to time.

Mass Appeal wanted more than just them to get respect, maybe even get paid a little, and make sure it felt like a celebration of the independent spirit. I am behind that 1000% of the time. Especially because it’s a serious (re: for profit) business at its core. Starving artists don’t survive. But, because it’s an entirely less scale-driven for profit, and more tell-our-friends’-stories to the world, before it’s too late, I think Mass Appeal will endure in a whole new way.

The blues never quite got that. Bonnie Raitt and others tried, but, it didn’t quite happen. Jazz went conservatory, which is still a blessing in its own right, but the art form lost a lot of its contemporary power in the process. Institutionalizing a scene will do that. And to be fair, the Boomer-era industry didn’t know any other way, and I get that.

Hip-hop, in all of its depth - from graffiti, to dancing, to DJing, to fashion, and yes, rapping, had a chance to do more, and Mass Appeal is executing on that chance beyond expectation.

Instead of trying to force the subculture into a college major or radio format to drive physical sales, they’re keeping it a subculture.

There’s an underground, a commercial presence, and a ton of room for any and all contributors to get in on the celebration, without any one artist or act owning the full economics of the scene.

It’s no surprise it took a Gen-X-run media platform that treats hip-hop as a living subculture instead of a heritage brand to make this click.

Which is a long and meandering way to finally bring us to the track “Madman” on the new Nas and DJ Premier record, Light-Years. I hear it as a song stretched across 5 decades. I could have picked a handful of tracks to argue the same point, and in the weeks ahead, maybe I will, but this one really stood out to me.

Here’s how “Madman” deftly pulls five decades of influence, lessons, and soul into a single song - bridging the 1970s all the way to today.

1970s. The movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Yes, the one with the mashed potatoes scene we got yelled at for trying to recreate every time there were mashed potatoes on the table. It had a crazy soundtrack, including a title theme by The Electric Moog Orchestra. The application of synthesizers and electronic instruments changed music and music production. Premier lifted the tracks core sample from here.

Note how the eerie and ethereal vibe (oh, we are getting to ether, don’t worry), contrasts the grounded vocals on the final product.

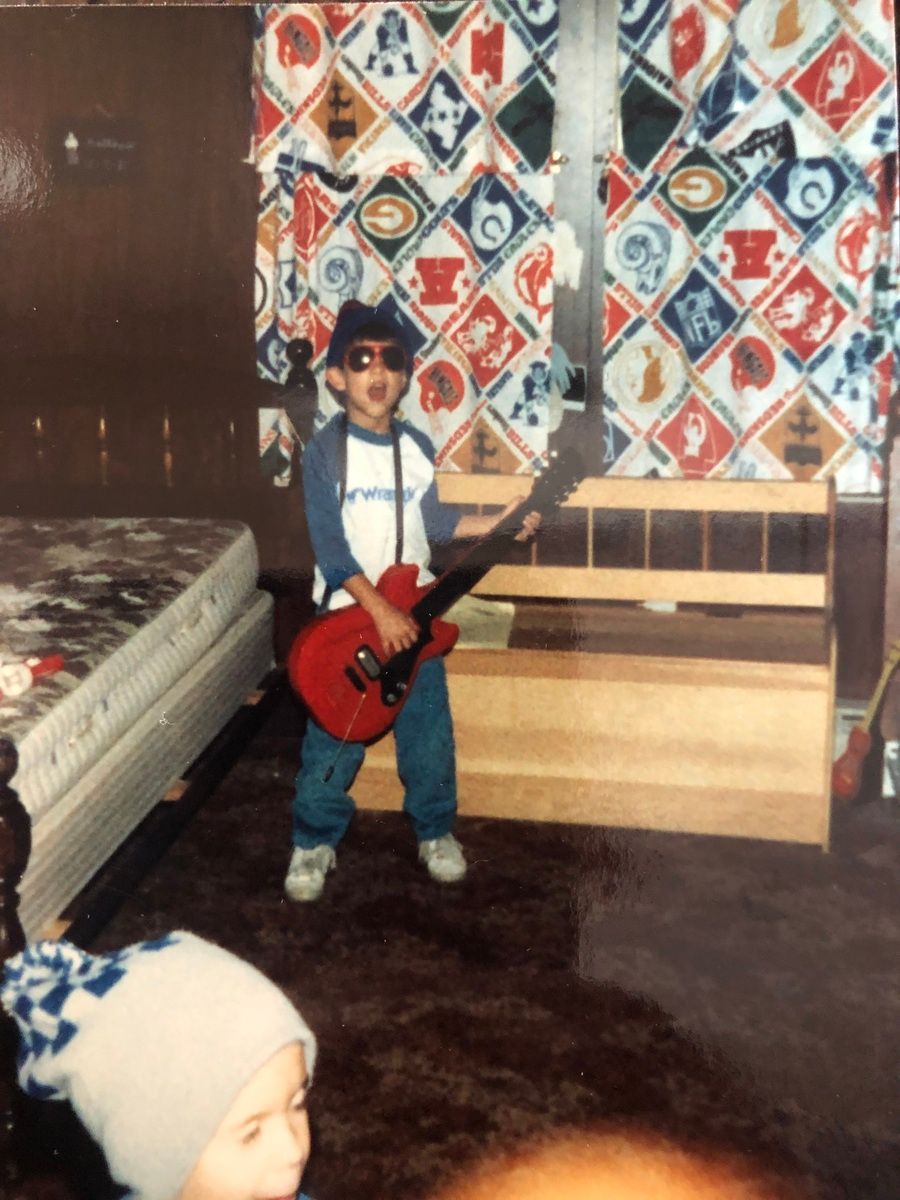

1980s. The rappers. And maybe most importantly, the evolution of rap styles that loomed large in a young Nas’ ears as park jam routines turned into a stylistic art form of its own. Rakim, with his softer inflection and poetic turns of phrase. Big Daddy Kane with his rhyme schemes and fashion. And, maybe most important in this case, Kool G Rap with his machine gun syllabic wordplay.

Note how Nas stacks his syllables and tell me you don’t hear that Kool G Rap DNA.

1990s. Yes, Nas shows up in the 90s, in force, but per the samples here, Wu-Tang Clan. Wu broke the record industry contract mold, first. The business of hip-hop would never be the same. As a callout, they’re the exact right sample layer here, because we’re going from non-traditional music creation and inspiration from the 70s movie synths, to explosive stylistic evolution amongst 80s rappers, to the business world shakeup of the 90s.

2000s. Look, it all went commercial. We felt it, we knew it, and we tried to make sense of it. The internet steadily killed off magazines and blogs replaced physical zines. Social media would take things over from there to make it even stranger. The world just got weird for the arts.

At the front end of the 2000s, Nas was on top of the world and making his run at being commercially viable beyond concerns about what would happen as rappers got old. Him and Jay-Z emerged as the businessmen in this era. What was great about hip-hop culture, was watching how “Ether” could evolve yet again into “Black Republicans” - beyond the bars, beyond the clinging onto who they were (re: calling the record Stillmatic was a sign), and setting up what was coming in the 2010s.

2010s. Mass Appeal happened. It almost feels destined at this point. In 2014, one of my top records of the year, and truly epitomizing the style evolution and business awareness at a level I will still get choked up when I express it, Run The Jewels 2 came out on the imprint. “Madman” exists because post Wu, post commercial rap, the spirit of independent art got proven out, in full, in this period - paving the way for what’s coming out now in the 2020s.

I have to at least say this part, too. El-P was running mail order scams on big box record stores in the early 90s to get Company Flow pressings out of New York. He signed to Rawkus. He left and founded his own label, Def Jux, later Definitive Jux because Def Jam got cranky even though the entire point of the name was to be definitively juxtaposed to the commercialized version of the art, and El-P would later tell us exactly how he felt about Rawkus and commercial art in poetic detail in “Deep Space 9mm”.

El-P is Gen X to the core. That energy - ripping off and remixing institutions from the inside out, traceable all the way back to his “independent as f***” ethos, made his joint collaboration with Killer Mike, Run The Jewels, a perfect fit for a Mass Appeal release in 2014 that, candidly, I still feel the aftershock of.

2020s. Between COVID and hip-hop turning 50, it all (finally) came together. The Mass Appeal concept was firing on all cylinders. Because they’d made the choice to keep their mode of hip-hop-business as a subculture, rather than turn it into a museum or conservatory, full of rigid rules and institutionalized snobbery, they emerged with a living, breathing ecosystem.

The Boomer run music industry was all about centralized brands and preserving/monetizing heritage brands. Think classic rock. Think the way jazz got conservatized. Mass Appeal didn’t do any of that. When the artists got past prime age, they asked themselves if they were still fans OR if they were nostalgic, and they chose fandom. If you can’t tell, my vote is there too. Fandom is the only choice for me here.

Mass Appeal focused on remixing those legacy institutions, flattening them out wherever possible, and building fiefdoms inside the culture. It’s not a top down thing. It’s not a nostalgic juke box thing. It’s not repackaging of the old for one more sales cycle. It’s new art, aware of modern times and tastes, with a subculture attitude.

You don’t get direct lines to modern rappers and originals stacked up like this for nothing. If you pay attention to nothing else but this snippet, notice how he stacks tributes,* business history, and a generational flex in one run here.

Let's cop acres, I do this for thinkers, salute to Sacha Jenkins

And door knocker fly ladies, Gucci link gangsters

And rappers that use one producer

You know that Metro Boomin and Future, we still don't trust you

Didn't start it but I boosted it, figured I'd bring it back since

Multiple hit makers on one album, I introduced it

In fact, everything in my head made bread

The LPs alone'll get me some Beverly Hills spreads

But still nothing is sweet, you can tell by just bumpin' this beat

Still Nasty since '91, nothin' competes

Before Snoop, before Wu, before Big

There was this young kid with small dreads from the Bridge

It's Nas

Preem, how many times I gotta tell 'em?

There’s no nostalgia in there. Pure, uncut, active fandom. I might even call it stewardship of a living culture.

That’s how 5 decades fit into a song. From movie sounds on new instruments, to early influences, to dominant eras, to post-success questions, with branching out updated influences, until you go all-in on the full fabric of a genuine subculture where telling your story becomes the only priority.

I truly respect what these guys are up to. We all have a jukebox in our pocket. No reason great artists can’t continue to put new classics into it.

Ps. maybe the song on the record that gives love to all sorts of members of the graffiti community is “Writers” (what a stunning tribute this is)

Pps. *With a heavy heart, we also have to say RIP Sacha Jenkins, who passed away earlier in 2025. Absolute legend. The quote line above is no doubt in the song with a ton of respect and a heavy heart. I hope he got to hear “Writers” (and I bet that song doesn’t exist with all those shoutouts without him or at least his friends’ influence).

Ppps. This whole Legend Has It idea makes me really happy.

Pppps. Since I said mass appeal this many times, I figure these are stuck in your head too: the Gang Starr track and Da Youngsta’s. Classics.