For years, I've been connecting with interesting people and documenting insights that might help my clients and myself. What was once private is now (mostly) public.

People often ask: "How do you know all these people?" and "How do you connect these (re: random) ideas?" The answer is simple: consistent relationship cultivation and thoughtful note taking. My north star is trusting my instincts, my maps are the constellations in these reflections.

This approach to multidisciplinary networking has helped dozens of clients, colleagues, and friends strengthen their networks and unlock new opportunities. Feel free to steal these ideas directly - that's what they're for! I can't promise you'll learn FROM me, but I guarantee you can learn something WITH me. Let's go. Count it off: 1-2-3-4!

Introducing... Aaron Gwyn!

Do you know Aaron Gwyn? He's a writer, professor, and musician - someone who grew up on a cattle ranch in Oklahoma, cut his finger off in a go-kart accident at nine years old, taught himself to write through obsessive practice, and now teaches creative writing at Oklahoma State University while publishing work across multiple genres. His writing appears in literary magazines and anthologies, and he's built a reputation as someone who understands that craft is earned through repetition, not talent.

If not, allow me to introduce you. Aaron is one of my favorite (and rare) combinations - of blue-collar kid who became a serious artist without pretending his origins didn't matter. He plays guitar, writes fiction, thinks deeply about fundamentalism (of all kinds), and has the kind of perspective that comes from growing up around real consequences and real limitations. He doesn't separate his ranching past from his literary present. He weaves them together - first-rate Faulkner style.

I wanted to connect with him because he represents something I value deeply: the understanding that scars aren't shameful - they're proof that you survived something, and they teach you lessons that unmarked skin never could.

Our conversation is LIVE now on the Cultish Creative and Epsilon Theory YouTube channels. Listen and you'll hear two writers from working-class backgrounds - a Wisconsin farm kid and an Oklahoma ranch kid - discussing how their childhoods shaped their art, why certainty frightens them, and what happens when you choose practice over talent, and humanity over ideology.

THREE: That's The Magic Number of Lessons

In the meantime, I wanted to pull THREE KEY LESSONS from my time with Aaron Gwyn to share with you (and drop into my Personal Archive).

Read on and you'll find a quote with a lesson and a reflection you can Take to work with you, Bring home with you, and Leave behind with your legacy.

WORK: Practice Compounds - Talent Is Overrated

"My grandparents put me in kickboxing when I was 11 and I was very focused on it and I put a lot into it, and I began to get good and I won tournaments. But I knew from that experience that if you practiced and practiced and practiced, that you would get good at something. And it was a matter of the time you sunk into it and the matter of a really obsessive practice. So when my friend Mark read my stories and said well, this works, but this stuff doesn't, I was like, oh, I just need to practice more. I want to complete this goal because I knew there's this reward on the other end of it."

Key Concept: Aaron learned early that mastery isn't about natural ability. It's about accumulated hours. Kickboxing taught him that getting hit and learning from it was how you got better. That same framework transferred to writing - when his mentor Mark critiqued his work, Aaron didn't feel rejected, he felt coached. The difference between people who succeed and people who give up isn't talent, it's the willingness to be bad for long enough that you become good. Most people can't tolerate that middle section. Aaron could because he'd already learned it in the ring.

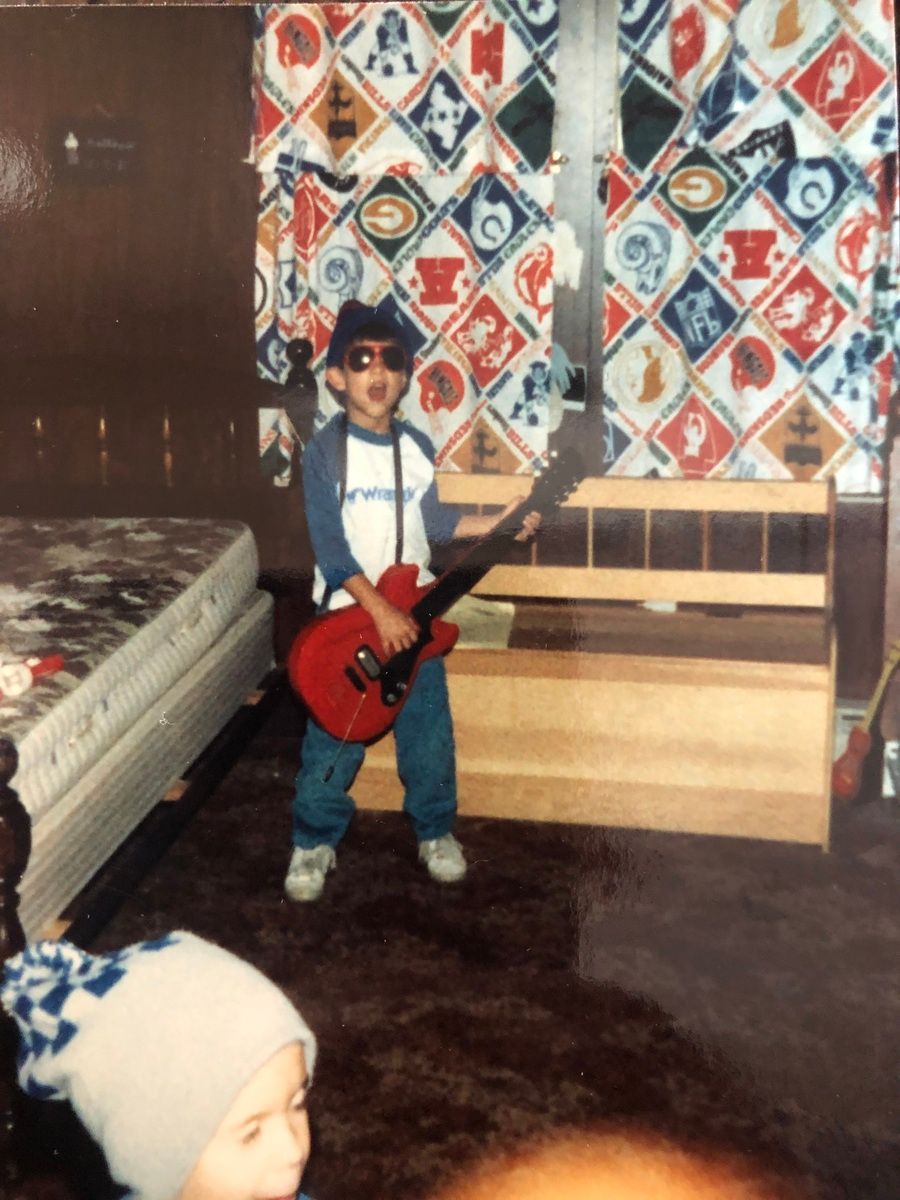

Personal Archive Note-To-Self: Sports and music and - anywhere you can get hurt and fail, ideally around peers, but in the presence of adults too, is ridiculously important. I remember the first time I was in over my head with a music thing. I was supposed to play with a group of others at church, at the encouragement of several adults, and there were just some chords that my little kid hands couldn’t quite grab yet (candidly, I was probably in elementary school, just really ambitious).

My mom had me call the guy, John, who was in charge of the make-shift music group, and tell him I wouldn’t be prepared for Sunday and I’d like to try another one. “No problem, I’ll get you the music for next time in advance so you can practice,” he said. I felt dumb as hell calling him and admitting I couldn’t do it. But he made it ok and you better believe by the next session I was ready.

Funny enough, I think the song was in a weird key and there was a lot of barring involved, which my pre-teen hands and high action learners acoustic were not doing me any favors there, but I took the failure and focused forward.

I think of that moment, of making the phone call and practicing to not have to make the phone call again, very, very often.

Work question for you: What skill are you avoiding because you're afraid of being mediocre at it for the next two years?

LIFE: Certainty Is A Fundamentalist Problem - No Matter What You Believe

"I began to meet more and more people who claim to be atheists, but were absolutely fundamentalists. They just didn't believe in God. They were fundamentalists about something else. And so then, once I encountered that among professors - people who are good people, people who are kind, people who are very intelligent and very well educated - but when it came to politics, I could see, well, this is religion."

Key Concept: Aaron was raised Pentecostal, left the church, and came back to faith on his own terms. So he recognizes fundamentalism when he sees it - not because of what people believe, but because of how they believe. The closed mind. The inability to question. The certainty that you have the answer and everyone else is wrong. He's watched intelligent, kind people adopt this posture around politics. It frightens him because he knows where that leads. The point isn't that religion is bad or atheism is good or vice versa. The point is: beware of anything that makes you certain you're right about complex things.

Personal Archive Note-To-Self: There’s an aspect of practice, meaning the failing and trying and slowly succeeding, where you learn forgiveness. And you don’t learn it in the abstract or poetic way you learn it going to church. I remember being a kid in church and hearing the bible stories and grasping the topic but - real forgiveness starts inside of you, with a comfort and awareness that you can be wrong and not only survive, but live long enough to be wrong again, and still keep making forward progress.

It’s hard to bridge that connection, between the learning of how to live and the actual practice of living life, but once you do, you don’t want to lose it. I experienced a million versions of what Aaron said here about recognizing fundamentalism in all walks of life. This hits too close to home.

In every case, what I see when I see someone acting religious about a topic idea, is somebody who forgot how to practice, and forgot what it feels like to fail. And, maybe most importantly, I see a person who forgot how ok and how part of life that is. You don’t have to have a single answer about life. You just have to be good. And try again tomorrow. Everybody who wants to make it more complex than that - good luck on judgement day, I guess?

Life question for you: Where in your own thinking have you stopped questioning because certainty feels safer than doubt?

LEGACY: Scars Remind Us The Past Is Real

"There's a passage in All the Pretty Horses where the character tells the protagonist that scars have the unique power to remind us that the past is real. And I think my finger and these scars remind you that the past isn't an idea. It's a reality."

Key Concept: Aaron can hold up his hand and show you the scar from the go-kart accident. The tendons still work. The bone still healed. It's a reminder that pain happened and he survived it. This isn't victim mentality - it's clarity. Too many of us try to transcend our past, to overcome it, to leave it behind. Aaron's point is simpler: your scars are real. They happened. They changed you. That's not weakness to confess, that's honesty to acknowledge. And when you acknowledge your own scars, you can see them in others. That recognition - that witnessing of what someone has survived - that's where real connection happens. That's legacy work.

Personal Archive Note-To-Self: I’m still thinking about the guy with the capo finger we talked about, if I’m being honest. That’s a - horrible to get, but very cool scar as far as I can tell. Maybe that’s what makes scars so much more interesting than tattoos, too. There’s a metaphor in there.

All I know is that life leaves its marks on us. Some are obvious and you can see them externally. Some are non-obvious and you can remember them, even when you’re trying not to remember them, sometimes. But those scars are part of what makes us us.

You know the thing about how everybody’s fingerprints are theirs and only theirs? Scars are like the fingerprints we get after we’re born. They suck to get. Sometimes they at least come with a good story. But they so make us us. They so have the power to shape who we become and remind us where we once were.

With a good side and a dark side, of course. For a kid who was raised around church and played a lot of music, my life feels a million miles away from both of those categories now, in all sorts of good, bad, and indifferent ways. However, from a pure scar (and muscle?) standpoint, I’m still building on both of those foundations every day.

There’s no easy way to make a hard call, but I know I can survive a hard call. There’s no easy way to refuse adopting the “one true way” of a system or process, and yet I’ll gladly pick my failing, practicing, self-inflicted methods to make my version of a collaborative jam out of life. These really are just the lived in skin version of fingerprints, and I’m sticking to that.

Legacy question for you: What scar from your past are you still pretending didn't happen - and what would change if you acknowledged it was real?

BEFORE YOU GO: Be sure to…

Connect with Aaron Gwyn on X/Twitter at @AmericanGwyn

Check out his writing and stories in literary magazines and anthologies, especially “Last of the Cowboys” on Panoptica!

Explore his work as a creative writing professor and mentor, particularly on Substack

Take a moment to notice what your own scars have taught you

You have a Personal Network and a Personal Archive just waiting for you to build them up stronger. Look at your work, look at your life, and look at your legacy - and then, start small in each category. Today it's one person and one reflection. Tomorrow? Who knows what connections you'll create.

Don't forget to click reply/click here and tell me who you're adding to your network and why! Plus, if you already have your own Personal Archive too, let me know, I'm creating a database.

Want more? Find my Personal Archive on CultishCreative.com, watch me build a better Personal Network on the Cultish Creative YouTube channel, and listen to Just Press Record on Spotify or Apple Podcasts, and follow me on social media (LinkedIn and X) - now distributed by Epsilon Theory.

You can also check out my work as Managing Director at Sunpointe, as a host on top investment YouTube channel Excess Returns, and as Senior Editor at Perscient.

ps. AI helped me pull and organize quotes from the transcript, structure the three lessons, and sharpen the Key Concepts. If you're curious about how I use AI while keeping editorial control and my own voice intact, I wrote about my personal rules here: Did AI Do That: Personal Rules